By Rachel Oswald, CQ Roll Call

MOSCOW — Nikolai Ponomarev-Stepnoi dedicated decades of his career to a U.S.-Russian effort to prevent nuclear proliferation.

Today, the retired nuclear scientist is glumly watching it all fall apart.

“The communication has been cut off to not even at zero but negative,” says the octogenarian, who was the first Russian scientist allowed to visit Three Mile Island after the 1979 reactor meltdown.

The former vice president of the independent Kurchatov Institute, one of the first Russian organizations to accept U.S. nuclear security assistance under the long-running Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction program, says nuclear security is too important to allow any spats to get in the way.

But that’s just what has happened. Ever since Russia’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, he says the two sides have gone out of their way to spotlight disagreements to justify why they have cut off almost all nuclear security work.

“Both countries should cooperate regardless of anything happening in Ukraine or anywhere else because it is too dangerous in the world not to,” says Ponomarev-Stepnoi.

In the first half of 2014, the Energy Department slowed down several joint projects with Russia’s state-owned energy company Rosatom that would have sent Russian scientists to U.S. government nuclear laboratories and vice versa for technical discussions on atomic reactor safety and non-proliferation. Then in late 2014, Moscow said it wouldn’t accept any more U.S. help in securing its large stockpiles of plutonium and weapons-grade uranium.

Congress too has made a 180-degree turn in this area. After more than two decades of funding joint U.S.-Russian nuclear security projects, lawmakers wrote into the fiscal 2016 defense policy bill a provision that would ban money for nuclear nonproliferation work in Russia. The Energy secretary would have the authority to waive that restriction. President Barack Obama vetoed the measure in late October without mentioning the issue, but the change shows just how far things have deteriorated.

The breakdown is part of a larger strategic fallo

ut, which has the two countries on opposite sides of two armed conflicts in Europe and the Middle East. Washington is pushing sanctions against Moscow and questions are being raised in both capitals about whether Russian President Vladimir Putin will pull out of a key Cold War-era arms control treaty.

The breakdown in nuclear security cooperation adds a new layer of risk and reignites fears of miscalculation and suspicion.

Senate Armed Services Chairman John McCain of Arizona says the Russians are clearly to blame. “When they cooperate, then I think we should consider the funding,” he says. “When they’re not cooperating, why should we waste the money on something we can’t get done?”

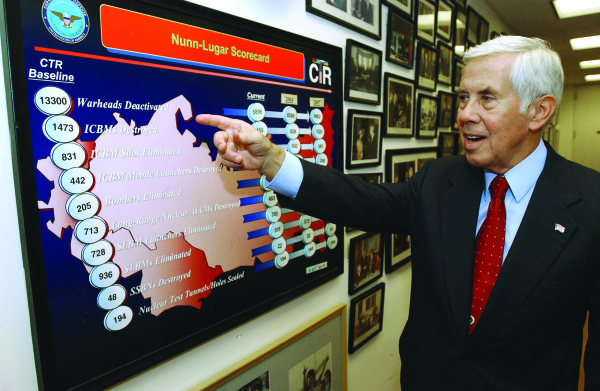

Even former Indiana Republican Sen. Richard G. Lugar, who along with former Democratic Sen. Sam Nunn of Georgia shepherded congressional passage of the Cooperative Threat Reduction initiative in 1992, is pessimistic about the outlook for the nuclear security relationship with Moscow.

“I think this is going to be a very important part of any relationship that we have,” he says. “It’s going to require a different frame of mind on the part of the Russians, which obviously is not there presently.”

Sleepwalking Toward Disaster

Interviews with nearly a dozen other senior Russian and American scientists, diplomats and retired defense officials reveal growing concerns that hard-won gains in post-Cold War nuclear nonproliferation are slowly being eroded. Russian and American officials still talk about the importance of working together to prevent nuclear terrorism, but there is no indication that either side intends to take steps to revive security cooperation and insulate it from other disputes.

Rose Gottemoeller, undersecretary of State for arms control and international security, says the administration is willing to resume stalled nuclear work, but Moscow has been dragging its feet.

“They’ve been good partners on nuclear security for the past 20 years so we continue to say, ‘Look, we’ve got a good record here. We need to continue and work together, ’” says Gottemoeller, who has worked on nonproliferation issues in the former Soviet Union since the end of the Cold War. “I have to say, though, that there is a real tentativeness on the Russian side right now about this cooperation. It’s related, I think, to internal political noise in their system.”

Republican Trent Franks of Arizona, a member of the House Armed Services Strategic Forces Subcommittee, adds: “It wasn’t America that stepped back from it. It was really Russia that pulled away from us.”

Many nuclear security advocates in Russia, however, don’t accept that the fault lies mostly with Moscow, arguing that both governments have erred in taking for granted the nonproliferation gains made in the last quarter century.

Alexei Arbatov, a former member of the Russian parliament who worked on defense issues, warns the two countries are “sleepwalking into a comprehensive and unprecedented crisis of nuclear arms control.”

Now chairman of the Carnegie Moscow Center’s nonproliferation program, Arbatov says the lack of understanding between the United States and Russia of the other side’s point of view has him losing sleep at night.

“I do not remember such a misunderstanding between Moscow and Washington since the early ‘60s,” says Arbatov, who sits on the Russian Foreign Affairs Ministry’s research council. “The situation changes, people change, generations change, and we may all once again find ourselves facing a new type of Cuban Missile Crisis.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia’s inability to pay for basic things such as fences and guards’ salaries at nuclear facilities led the United States to step in and help.

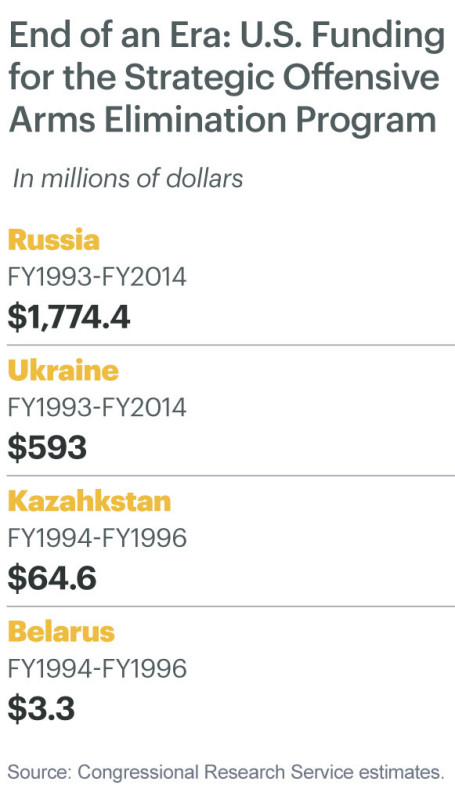

Starting in 1991, the Nunn-Lugar program spent billions of dollars in Russia, mostly through Defense Department-administered contracts that destroyed thousands of Soviet-era nuclear warheads and more than 1,000 long-range missiles, as well as dozens of submarines and bombers.

The money also went to help keep Russian nuclear scientists employed and to improve Russia’s accounting practices for its millions of pounds of highly enriched uranium and plutonium. The program expired in 2013.

Can’t Trust or Verify

Some U.S. officials and analysts privately say they are concerned that the longer the Russian economy deteriorates, the greater the temptation will be for the Kremlin to shortchange nuclear security projects, such as needed computer software updates at civilian sites housing nuclear materials. Moscow has said it can pay for all needed upgrades and site work on its own, but U.S. officials worry that they have no way of verifying that Russia has made good on its word.

“That is a continuing problem and why we have stressed to them that we need to continue to work together,” says Gottemoeller.

A Western official in Moscow who insisted on anonymity acknowledges that Russia’s economic situation today is not nearly as severe as the tailspin of the late 1980s and early 1990s. But the fears linger.

“What I think my greater concern would be … is even when the Russians make something their priority, these days there’s so much corruption and so much inefficiency that they’re really bad at it,” the official says, noting that even major prestige projects such as Russia’s space program have rockets blowing up on the launch pad or failing to reach orbit. “So my concern would be less the resources, more their ineptness.”

Tom Marino, who sits on the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia and Emerging Threats, says the United States would be foolish to count on Putin to protect Russia’s nuclear materials from would-be traffickers.

“Russia has so much nuclear material missing, they just don’t pay attention to it,” says the Pennsylvania Republican, who is also the vice president of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly. “I don’t know if they don’t care or if it is just that they are so disorganized over there.”

Comments like these infuriate Russians working in the nuclear security realm.

Anton Khlopkov, director of the independent Moscow-based Center for Energy and Security Studies think tank, says it is “humiliating” and counterproductive for the United States to question Russia’s commitment to nuclear security.

“I see that this perception in the [United] States is very strong, that the level of nuclear security in Russia is still not appropriate,” Khlopkov says. “I cannot accept that.

Khlopkov, a nonproliferation analyst and editor-in-chief of the journal Nuclear Club who has written policy briefs for the Stanley Foundation in Washington, says that if the United States is so concerned about deteriorating nuclear security standards in Russia, it should investigate how the billions of dollars in Nunn-Lugar activities were spent, since much of the work was handled by U.S. contractors and only concluded two years ago.

Anne Harrington, who heads up defense nuclear nonproliferation work for the Energy Department’s nuclear weapons branch, says her office is ready to resume work with Russia under a 2013 agreement that would have each side co-finance nuclear security projects.

“We continue to engage at a technical level in areas of nonproliferation and threat reduction to the extent basically that the Russian government will allow us to,” Harrington tells CQ. “That really is the constraining factor.”

Congressional Hurdles

Even if Obama finds a way to smooth over serious differences with Putin over Ukraine and Syria to reinvigorate nuclear security, he would face considerable hurdles from staunch Republican critics.

House Armed Services member Michael R. Turner rejects the idea that more money will solve Russia’s feared nuclear security problems, which were highlighted recently by news reports that Moldovan authorities have conducted several sting operations in recent years that turned up lethal quantities of radioactive material offered up for sale by smugglers with possible Russian connections.

“This is an issue of Russia having lax systems and needing to step up to the plate,” the Ohio Republican says. “Russia has all of the resources that it needs to undertake its own control of its nuclear materials. They’re in Syria using their military. They’re in Ukraine. This is not an issue of lack of resources.”

Democratic Sen. Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts is one of the few voices on Capitol Hill continuing to call for a revival of the nuclear security relationship with Russia.

“It’s important for President Putin and President Obama to be talking at all times, especially about nuclear issues, because ultimately those kinds of weapons slipping into the hands of non-state players can wind up causing a catastrophic global situation,” says the Foreign Relations member. “The job is not yet done; we have to ensure that the United States and Russia remain committed to securing any and all nuclear materials.”

The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting provided support for this report.